SIRU 2.0 Case: Humanium Metal

SIRU 2.0 is financed by by Tillväxtverket with EU funding, and by Region Jönköpings län.

"The Most Precious Metal on Earth"

Case Author: Mark Edwards Opens in new window.

This case presents the case of the social innovation Humanium Metal and its parent organization, Individuell Människohjälp or IM Swedish Development Partne External link, opens in new window.r, and two IM entrepreneurs who were intimately involved in the founding and development of the Humanium Metal venture. The case materials were collated from online sources and from interviews with two IM entrepreneurs Simon, Business and Innovation Manager for Humanium Metal and Jaqueline, Program and Advocacy Lead for Humanium Metal. From our analysis of these sources, insights are developed into how the leaders overcome obstacles to express their core values in powerful and persuasive ways. The case provides insights into the alignment between personal commitment and organizational purpose and mission.

Humanium Metal is a social innovation begun by its parent organization IM which is a Swedish international development organization working in the fields of poverty elimination, social inclusion, and sustainability. It was founded by the Swedish social entrepreneur and politician Britta Holmström in 1938 as a response to the growing humanitarian crisis in Europe. IM grew rapidly during and immediately after World War II and provided support for the many refugees and victims of that tumultuous conflict. Since then, the work of IM has concentrated on collaborative projects and the individual worth of every person as a counter to the oppression and violence that often results from ideological conflict and systemic corruption. IM works with all levels of society to create social, economic, and environmental initiatives that target the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Currently, IM has established operations in many regions of the world including Central America, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southern Africa.

Humanium Metal (HM) is a social business enterprise initiated by IM. HM’s mission is to reduce gun violence by recycling weapons into metal products and using the revenues for peace-building and justice programs. The purpose of HM is to:

[E]mpower and support survivors of violence, giving them strength, knowledge and confidence in themselves to stand up against violence. Youths reclaim public spaces as violence-free zones and mobilize their communities to unite against violence. (Humanium Metal, 2020)

Knotted Gun sculpture

In effect, HM’s mission is to transform violence into beauty, to recycle gun metal into something that communicates peace through aesthetics and artistic design. Gun violence is a destructive and terrorizing force in both advanced and impoverished countries. Gang warfare, illegal militias, and organized crime syndicates can cause immense harm in communities where guns are easily available. Sometimes governments implement weapons destruction programs, gun moratoriums and seizure programs in affected regions and stockpile the gathered weapons. HM breaks down these stockpiles of weapons, extracts the metal, called Humanium Metal, and transforms it into metal ingots and metal powder. It then engages with businesses, entrepreneurs, designers, and artists to develop products such as watches, jewellery, machines, and works of art. HM products are designed and marketed as “commodities for peace” so customers are informed of the HM mission and can feel that they are contributing to its mission.

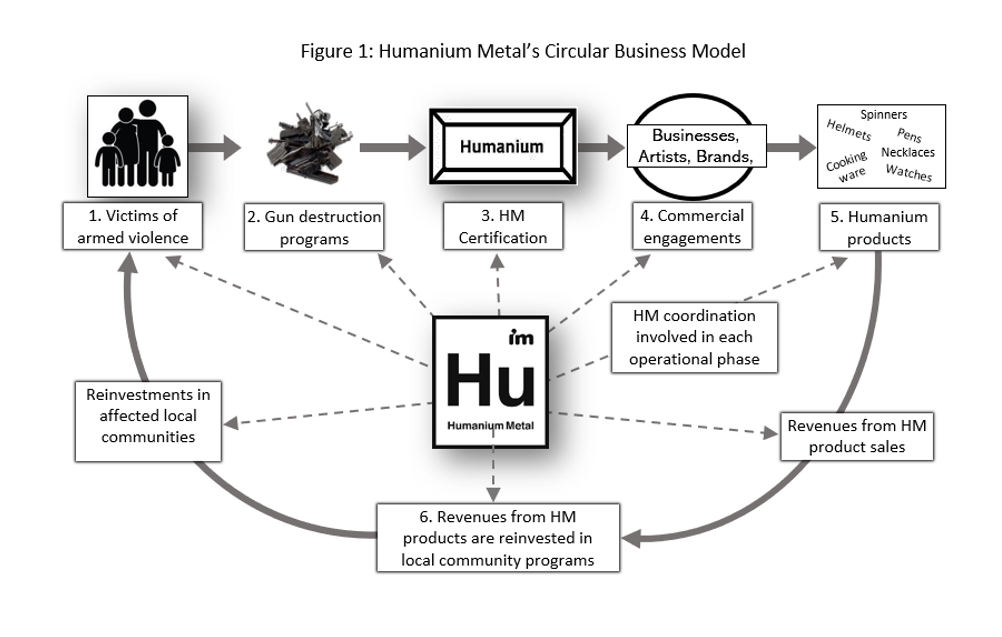

HM was first produced in 2016 in El Salvador, with firearms seized by the Salvadoran government. El Salvador was chosen as a pilot-region for the business, as the country is heavily affected by high levels of armed violence. There is also strong support at many levels of society to address this issue to achieve inclusive socio-economic development in the region. In 2018 HM expanded further into Zambia and the United States of America. Humanium Metal offers a strong voice against armed violence in the USA, where access to weapons is often seen as the simple solution to complex problems. IM believes that access to weapons is one of the fundamental problems facing all communities especially those in developing nations. Figure 1 shows the basic outlines of the HM circular business model. The most common method for producing Humanium Metal is through government seizure programs. Illegal firearms are “destroyed” and the metal melted down and turned into ingots, wire, or pellets. The metal is sent to Sweden and reduced to a powder that can be more easily used in the 3D printing production of metal products. Examples of products using Humanium Metal in their manufacturing include watches, pens, spinning tops, buttons, bracelets, and headphones.

The income generated is re-invested into communities affected by gun violence and so aims to break the vicious cycle of violence and poverty. Host community activities funded from the business’s profits include supporting survivors of armed violence with income generation, empowering communities to reclaim public spaces as violence-free zones, empowering youths to choose violence-free paths, and supporting communities to advocate for legislation that prevents gun violence. The revenues flowing from the overall sale of HM products have exceeded 5 million US dollars since the beginning of the enterprise. The income generated for societal change has now exceeded 1.2 million US dollars with all this money being channelled to HM community partners. The business activity of upcycling a commodity used for violence and killing into consumable goods for peace creates a platform for a global movement for peace and security.

The HM Business Model and Circularity

With such intense human justice, community safety and physical security issues in play, ethical dilemmas and opportunities frequently arise in the HM workplace. Figure 1 shows that multiple stakeholders are intimately involved in the social-ecological value network[1] of the HM business model. One interesting feature of the circular nature of their value network is that HM aims to reduce the need for guns in the same neighbourhoods where they come from. HM is investing in a process they hope will result in a diminishing supply of the essential input material, that is, metal from guns. This goal will, of course, disturb the organized system of violence and illegal economy that currently impacts the communities where guns are collected. For some, fewer guns will mean diminished power and that can cause conflict. So, working with HM is not without its risks and this is even more true for the local coordinators and volunteers who are actively involved in the community reinvestment programs.

There has been a terrible parade of contributing factors to the ongoing community violence that harms local community life. The postcolonial impact of institutionalized violence, decades of government neglect, lack of economic stability, geopolitical trickery, violent foreign intervention, political instability, the ready availability of firearms and more recently the destabilizing effects of climate change combine to produce a deadly cocktail of destabilizing intimidation and violence. Even amid all this however, communities are still full of life and demonstrating resilience to partner with local and international agencies to seek solutions. Breaking the cycle of violence with the recycling of gunmetal, however, challenges the established power order and can therefore upset the organized centres of corrupt political and gang power. But the benefits are so transformative that local groups, affected families, courageous individuals, and community leaders are willing to take the risks and work with HM to create the social benefits that flow from the HM business model. This is a powerful form of social regenerativity. Regenerative sustainability goes well beyond reducing carbon emissions of harming the environment and actively seeks to revitalize natural systems through innovative and restorative practices. Social regenerativity aims to do that for human communities.

[1] We use social-ecological value network as a more accurate term for the web of human and ecological relationships that all companies are immersed’. The usual jargon of “supply chain” simply does not capture the profound interpenetration of biophysical systems that underpins all elements of economic production and consumption. The systems that HM is working with are not just about mechanical chains of supply and demand pressures. The human and the ecological are intimately interconnected in multilayered networks, not linear chains. The environmental, communal, and ethical factors involved in their work are complex and inclusive of all kinds of emotional, ecological, intellectual, physical value that cannot be reduced to the economic forces of linear supply and demand models.

David’s Story

The notion of regenerative sustainability takes on profound meaning in the context of the HM circular business model. Take the case of David from Central America. David was a boy of twelve getting up early to go to work one day when, just as he stepped onto the street outside his family home, he was shot. No rhyme or reason to it, just pure, purposeless violence. The gun was there, the perpetrator’s unknown story of abuse and violence was there, and David was left in the street hanging grimly onto his life. The gunshot had torn through his spinal cord and left David with paralysis in his lower body. With the support of his family and community and financial support from HM, David slowly recovered and went home to learn how to live with his wheelchair. But David has immense courage and spirit and soon began to work towards his dreams and put his entrepreneurial business skills to work. He sells street wares in the local towns from his wheelchair and is now saving money for his further education and business ventures. HM supports the victims of gun violence like David and his family. They provide funding but also training and skills development to help families recover from violence and lead lives that they are proud of. All this takes creativity and determination, qualities that characterize all the HM staff.

Social dilemmas as motivating opportunities

While there will be strong alignment for many of the views and goals of the many different actors involved in HM’s social-ecological value network, conflicts will always arise. There can also be confounding problems in the multiple goals that HM aims to achieve. For example, one area that has been difficult for HM staff is the contentious issue of the environmental impact of the smelting of weapons. Turning the gun metal into something that can be of value for crafting high-quality jewellery is a costly and energy-rich process that consumes a lot of energy and produces copious amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Even when alternative energy sources can be found the environmental impact of the manufacturing, transportation and packaging processes can be significant. HM staff work actively to minimize these aspects of the HM value networks and uses these constraints as motivation for further innovation. The occasional misalignment between environmental and social sustainability spurs her towards finding solutions.

HM and the Three Pillars of Regenerative Sustainability

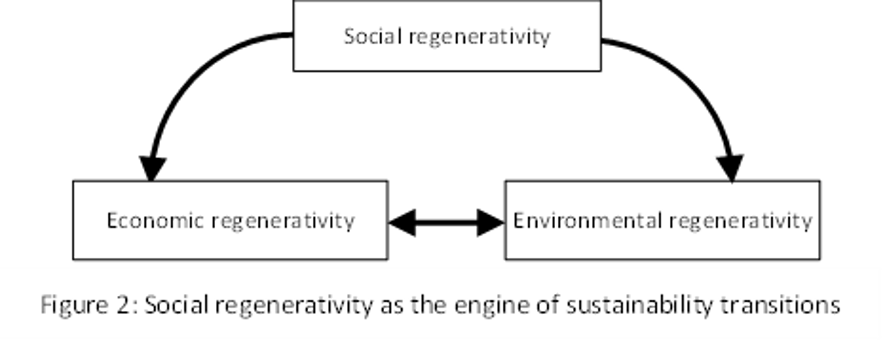

The HM enterprise and the entrepreneurs that lead and direct its activities, portray the social sustainability side of regenerativity. Regenerativity has typically been presented in the sustainability literature as having a predominantly environmental focus. This is not surprising given the heightened awareness and increasing urgency of environmental issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss and impending tipping points in crucial Earth biophysical systems. HM, however, places its focus on regenerating human communities by removing weapons and reinvesting in neighbourhood security, education, and employment. This is usefully seen as a social form of regenerative sustainability. Interestingly, IM, HM’s parent organization, supports sustainable farming and community gardening programs in these same communities to improve food security, nutrition, and skill development. The aim is to have regenerative impacts on both human and ecological communities. HM presents an interesting case where the three pillars of sustainability – the economic, the social and the environmental – are each treated from a regenerative perspective. The social regeneration of communities drives the three pillars of the sustainability transition process (see Figure 2). Regenerating communities’ social well-being results in all those social benefits that flow from greater neighbourhood security including education, gender issues, increased personal freedom and political empowerment. This social regenerativity drives economic regeneration through improved security and freedoms allowing economic activity to expand, people can move and work more freely, and offering alternatives to the destructive problem of young people being drawn into lives of violence, corruption, and organized criminality. Finally, social regenerativity drives the environmental regeneration that comes when people can move safely to tend to their neighbourhood gardens and produce food locally. Figure 4.2 depicts these dynamics that flow from HM’s focus on social regenerativity. The cascading benefits that accrue economically and environmentally would not occur without the circular social regenerativity that the HM business models enable.

Being a regenerative entrepreneur in this social context of ‘three pillar circularity’ means that personal stories, histories, and purposes can be drawn on to create multiple forms of benefits that restore the resilience of natural and social systems. Circularity is frequently portrayed as a technical strategy for developing sustainability, but in this example, we see the power of social circularity and the kinds of sustainability and ethical competencies for building the social infrastructure of a very innovative form of circular business model.

Regenerative Purpose

The HM business model not only injects regenerative social sustainability into the communities it works with, but it also brings a regenerative and revitalizing balance to all the stakeholders who are involved in the enterprise. Working in the international development and sustainability fields can be a draining if not exhausting vocation. While this is true of the HM enterprise, there is also a rejuvenating side to the work that restores faith in people and in the power of community resourcefulness. Regenerativity is not only about revitalizing the exterior worlds of ecologies, communities, and economies. It is also about regenerating the interior qualities that power personal inspiration and commitment.

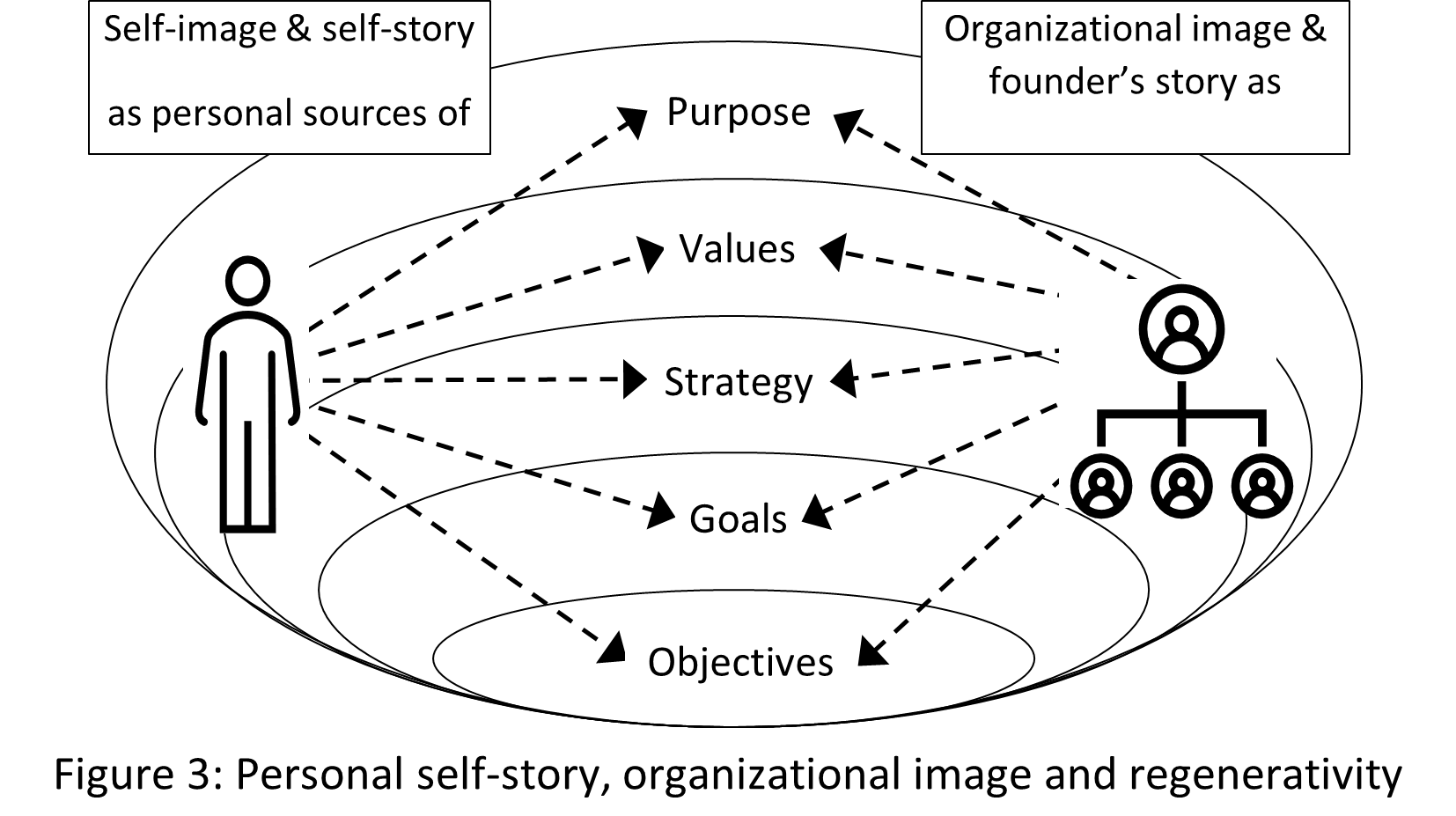

HM places a big emphasis on developing staff’s “self-leadership” capacities. For staff to define and develop “their own priorities and goals” these objectives ultimately become the orienting framework to work towards. These interior goals become as, or even more, important than the formal organizational goals of KPIs. The regenerative power of the work of HM operates at all levels from the specific task objectives and program goals to the business strategies and business models through to the guiding values and overall mission and purpose of the enterprise. Figure 3 draws attention to how the entrepreneur’s personal backgrounds invigorated each of these work levels.

Emancipation, Regenerativity and Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship has been likened to a form of emancipation that frees people from the constraints of the status quo. For example, Rindova, Barry and Ketchen (2009) take the perspective that:

Viewing entrepreneurial projects as emancipatory efforts focuses on understanding the factors that cause individuals to seek to disrupt the status quo and change their position in the social order in which they are embedded (Rindova et al., 2009, p. 478)

The HM enterprise can be seen as disruptive not only related to the violent systems of corruption and criminality that characterize the suburbs and towns that it operates in. It is disruptive of the culture of weapons manufacturing, the geo-political causes of community violence and the flow of drugs, illegal financial proceeds and human trafficking that cut across international borders. Ultimately HM is disruptive of the feeling that problems always lie elsewhere and that we are not intimately connected. The global nature of the HM circularity model disrupts the view that the economy sets the contexts and priorities for society. For example, extractive economies not only instrumentalize nature and ecological systems, that is, consider them as resources for making a profit, but they also instrumentalize ‘human resources’. In Triple Bottom Line terminology, extractive economies, whenever it is legally possible, prioritize profits over people and the planet. The social regeneration model of HM flips these priorities. It does not leave profit or financial responsibilities out of the picture but sets human communities as the benefit to be priorities. The socially and ecologically extractive approach that underpins a significant proportion of international trade is disrupted by HM’s offer of socially regenerative forms of renewal. This injection of regenerativity extends stakeholders’ sense of connection and responsibility towards other individuals, other communities, towards future generations, irrespective of where in the circular loop of regeneration they might be.

References

Humanium Metal. (2020). The Striker. IM Swedish Development Partner, Online, Retrieved from https://humanium-metal.com/our-impact/

Rindova, V., Barry, D., & Ketchen, J. D. J. (2009). Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 477-491. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=40632647&site=ehost-live

Sternad, D., Kennelly, J. J., & Bradley, F. (2016). Digging Deeper: How Purpose-Driven Enterprises Create Real Value. Austin, Texas: Greenleaf.